This is my story about the strange and eventful year that was 1966.

It took me all the way from a bungalow on the volcanic lava slopes of Auckland/Tamaki Makarau, to a haunted Elizabethan cottage in East Anglia and back again.

In 1966 I learned that the world contained many things that didn’t make sense.

In February 1966 I celebrated my fifth birthday. Straight after that I started school, as is the custom in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Maungawhau Primary School was walking distance from our family home in Plunket Road.

I was the eldest of my parents’ three children and the only girl. I had to do everything first.

Starting school felt like just the right amount of challenge. I was getting familiar with the routines and I was making friends. I loved the times when three classes came together in the hall for music and singing.

But this was just the first of many big changes for me in 1966.

After I’d been at school for a few weeks, suddenly one evening my brothers and I were bundled onto an overnight train bound for Wellington. It was such a rush that none of us had shoes.

In the morning our father took us to Wellington Zoo, but that wasn’t the reason for our visit.

Later that day we boarded a huge grey ocean liner called the Northern Star. I discovered that the ship was taking us all the way to England. My father’s parents lived there.

My parents had sold their car to pay for our family’s round-trip tickets. In 1966 a round-trip ticket for one adult was 386 pounds. The VW Beetle had been a gift from my mother’s parents, when my youngest brother Kenneth was born.

Above: Family being stalked by giraffes. Me and my brothers at Auckland Zoo with our mother, Sue, shortly before we boarded the ship for England. From left: Alice, David, Sue and Kenneth.

A land of sheep and butter

Aotearoa-New Zealand in 1966 was a quiet backwater in the remote South Pacific. There were far more sheep than people.

The New Zealand economy was strong, based on food exports, and incomes were egalitarian. it was described as an ideal place to bring up children.

My parents were both academic migrants. My mother had arrived on a Fulbright Scholarship from the USA in 1957. Here’s more about Sue. My father had come from England, via Australia in 1958, to take up a job teaching anthropology at the University of Auckland. Here’s more about Ralph.

New Zealanders munched their way through huge quantities of meat and home baking. Butter consumption was an incredible 20kg per person per year, most of which probably went into all those scones and cakes.

The local political scene was pretty stable. Keith Holyoake’s conservative National Party had just won a third consecutive election.

Also in 1966, the Maori Queen, Dame Te Atairangikahu, began her iconic 40-year reign.

New Zealand was far, far away, but not forgotten. Governments of bigger countries were keeping a watchful eye on New Zealand. In 1966 US President Lyndon Johnson and Vice President Hubert Humphrey both made visits to New Zealand to ensure support for the war in Vietnam.

And in 1966 the French government started testing nuclear bombs in the South Pacific.

Six weeks on a smelly boat

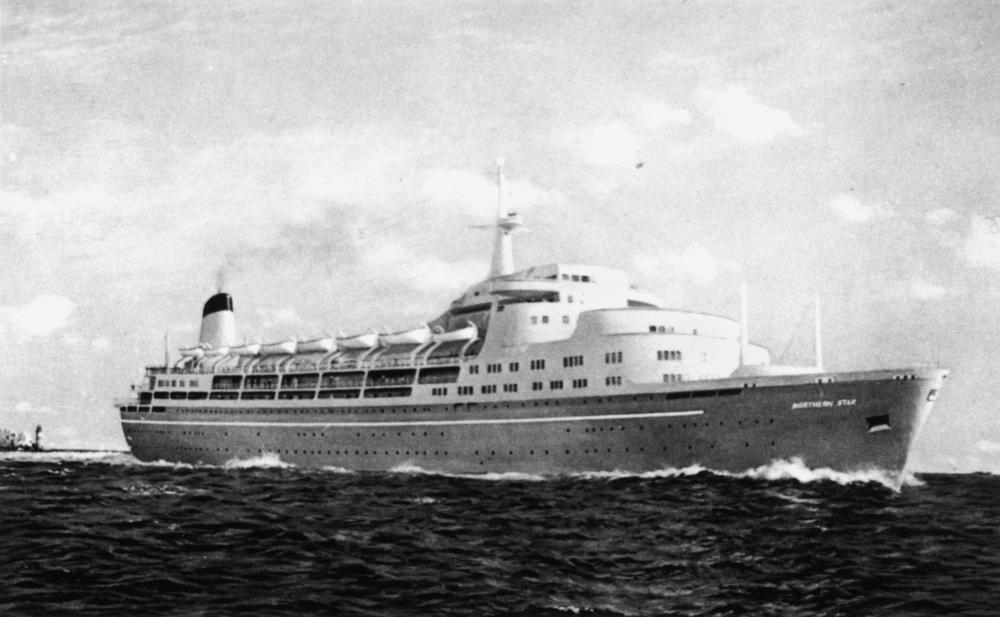

The Northern Star was a one-class ocean liner built to carry live human cargo. It circled the globe several times a year. On the voyage south from Britain, the ship was full of fare-assisted migrants emigrating to New Zealand and Australia.

On the return voyage the ship was laden with economy minded travellers making the trip back to what most Pakeha (white) New Zealanders still regarded as the “homeland”.

The Northern Star was not a thing of beauty, and it reeked of diesel. On www.nzmaritime.co.nz, Scott Baty describes the Northern Star aesthetic as “formica and linoleum”.

My family had a small windowless cabin down many staircases. Like a school camp, the cabin contained two bunk beds with squeaky plastic mattresses. This was considered suitable for our family of five.

My parents were distraught to discover that there was no separate cot for my 16-month-old brother Kenneth. When they paid for our tickets, they had been assured there would be a cot. There was nothing that could be done.

This situation might not have been a problem for families who were used to sharing beds with their children. But my mother had a lifelong sleep disorder. And my father was so huge that the bunk wasn’t big enough for him. It creaked ominously whenever he lay down.

My brother David (aged three) and I had to sleep in the top bunks. The light stayed on so our insomniac mother could read.

Above: The Northern Star. That’s me, just above the waterline, staying afloat. Photo in John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Public Domain

Alice at sea: too big, too small

On the Northern Star I was a problem, for the first time in my life.

The ship was full of children, but I didn’t find any playmates. I had just turned five, and I was tall for my age. Every time I went with my mother and brothers to the younger children’s play area I was asked to leave.

I was supposed to spend my days in the school, which was a big noisy room full of rowdy older kids and teenagers. Parents and younger children weren’t allowed in the school room. Nobody paid any attention to me, sitting in my silent terror.

I’ve met people who travelled on the Northern Star as kids and had the happiest time of their lives. For them it was a wonderful family holiday.

But my parents lived for their work. Neither of them would have considered the possibility of enjoying family time on a ship. The lack of sleep probably didn’t help their attitude.

The endless engine noise was grinding all night in our little room. The toilets on our level were a long way away. I couldn’t even go to the bathroom on my own.

Also, with no shoes, my brothers and I failed the dress code for the dining room. But they couldn’t ban us from eating for the whole six weeks.

This was my first encounter with institutional food. Breakfast time featured the aroma of stale eggs.

When the ship reached the Panama Canal, my father took off for a conference in the northeast United States.

Many people on the ship assumed my mother had been abandoned. It was sort of true. But it did mean there was more space in our little bunk room.

Stonehenge and chocolate

Finally, barefoot and yawning, we arrived in the British Isles.

My aunt Rosemary, my father’s sister, came to meet us at Southampton. Both my mother and I knew and loved Rosie. She had been visiting New Zealand at the time of my birth, before she returned to England to get married and start her own family.

We celebrated our arrival with a visit to Stonehenge. Rosie understood that archaeological sites were a priority for my mother.

I walked up to one of the huge Neolithic standing stones and laid my hands on it. These days there are fences to protect the monument from people like me.

Stonehenge gave me an amazing feeling of awe. I felt I was in the presence of something huge and old and important. I didn’t have anyone to talk to about my experience, so I filed it away in my memory, on a shelf labelled “mysteries”.

Many years later I found a word for it: numinous.

Here’s German theologian and philosopher Rudolf Otto’s definition of numinous: “arousing spiritual or religious emotion; mysterious or awe-inspiring.”

After Stonehenge, Rosie took us to her home in Thornbury, near Bristol. I met my two little cousins, Ruth and Rachel, and their older half-brother, Paul, and their dad, Ross.

Everyone was excited to see us. Also, my father reappeared.

It was Easter weekend. I was having way too much fun. I overdosed on chocolate Easter eggs.

Later that day, on the way to Shropshire, I lost my chocolate on the cream leather back seat of my grandfather’s brand new car. I wrecked my chances of a good relationship with my grandfather. Although my lack of shoes had probably already done this. Read more about this sad story here: Dorothy and her ancestors

Welcome to these ancient isles: Stonehenge was the first thing I saw after we landed. Stonehenge photo by Stefan Kühn, CC BY-SA 3.0

Cool Britannia

In 1966 Britain was a happening place. Harold Wilson was Prime Minister, and the British economy hadn’t yet fallen over. Also, England won the World Cup.

It was the high point of the flowering of British pop music, just before psychedelics took over. London was swinging to the sounds of “Sunny Afternoon”, by the Kinks, and “Paperback Writer”, by the Beatles. Carnaby Street was full of young people in colourful costumes, having fun.

But my parents were in their thirties. They had three little children: me, aged five, David, aged 3, and Kenneth, aged 18 months. The only place any of us was going to be swinging was at the local playground.

A haunted playhouse

After our visit to Shropshire, our family headed for Cambridge.

Our first new home was a cute 16th century cottage with a thatched roof and roses in front. It was way out in the countryside. It belonged to one of my father’s old university friends.

The cottage was sized like a playhouse. The doors and ceilings were far too low for my ridiculously large father (he was over 6 foot 6).

I‘m pretty sure it was haunted. There was just a feeling that the place was occupied by something other than my family. And all night, the cottage creaked in a scary way.

Also, like all antiques, the cottage was fragile. Things came apart when I touched them. One night a huge rafter beam fell off the ceiling next to my parents’ bed.

We moved out before the roof collapsed on us.

Above: This is what the haunted cottage looked like. It didn’t look scary by daylight. Photo credit: Andy Morffew from Itchen Abbas, Hampshire, UK, CC BY 2.0

Ralph’s happy place

Soon we were living in a post-war duplex in Chesterton, in the outer suburbs of Cambridge. It was cramped and it wasn’t picturesque, but the door frames were bigger. Also, there were no ghosts.

Our home was in Water St, a block from the River Cam. The Green Dragon Inn was down the road. Across the Green Dragon bridge was Stourbridge Common, a huge open space with gypsy caravans and tripping hippies.

My father, Ralph, had been a student at Cambridge and he was very attached to the place. He had lots of friends and colleagues.

Our family was in Cambridge because my father was on a sabbatical year. After every seven years as a university lecturer, he could take one year off teaching, so he could do some writing and research.

1966 was an important year for Ralph, creatively and professionally. He spent his time at Cambridge dreaming up “Why is the Cassowary Not a Bird?”.

This was the year Ralph hit his sweet spot and established his authority as an ethnobiologist. Here’s more about Ralph: My father the giant

For more about cassowary dreaming, see here.

Wives and other women

To my American-born mother, Sue, Cambridge was an alien world. It was much stranger than she had expected. (And she’d run archaeological excavations in the New Guinea highlands!)

Sue had accompanied my father on his sabbatical trip, expecting that as an academic in her own right, she would be included in the Cambridge collegial atmosphere. But she hugely underestimated the institutional sexism of Cambridge. As an Ivy League-educated American woman, she had no way of knowing about this in advance.

My father didn’t make much effort to introduce Sue to potential colleagues. It’s possible that it was out of his hands. Wives were banned from college dinners and other events.

At one particular wife-free evening, my father was introduced to the Australian feminist activist Germaine Greer. Germaine was allowed to be there, because she wasn’t anyone’s wife. When Sue found out, this delayed her conversion to feminism by many years.

I’ve written more about Sue here. And here.

Above: The River Cam from the Green Dragon Bridge. It was only a block from our house, but I didn’t see it much because I had pox. Photo credit: FinlayCox143, CC BY-SA 3.0

Itchy and scratchy

While Ralph was dreaming of cassowaries, Sue was stranded in Chesterton with three young children, no friends, no support network, no family, no money and no car.

She was approached by friendly women, wives of academics. But Sue wanted to talk about archaeology, not babies.

Things didn’t improve.

As soon as I started school, I became a plague carrier. One by one I contracted mumps, measles and chicken pox from kids in my classroom. And passed them on to my brothers, in succession.

My Californian grandparents came to visit, but I didn’t see them because I was so sick. I can remember the agonizing, itchy, revolting pustules. And then the achy misery of mumps. And then the fierce hot rash of measles.

There was also chronic bedwetting, exacerbated by unsympathetic teachers (in the short periods in between sickness) and bullying.

And then David ran through a glass sliding door and had to get his chin stitched up. And Kenneth ran himself a hot bath and got third-degree burns. It went on and on.

Yellow like a submarine

Finally, one weekend we were disease-free enough to make a short trip to Wales to meet my Welsh great-grandmother, Caroline Bulmer, nee Hughes. “Granny Holyhead” was the family matriarch. She was 91, a tiny, smiling, wrinkled woman, the oldest person I’d ever met.

I was fascinated by her Victorian upstairs bathroom. The flush toilet was a huge wooden throne. I broke the antique pull chain. I was leaving a trail of destruction through the British Isles.

A few weeks after we visited Holyhead, we heard that Granny had died. I hope she didn’t catch something from me. We inherited Granny Holyhead’s television and her elderly car.

The huge ancient television, which had its own wooden cabinet, was installed in our cramped family room. My mother made us watch TV so she could have some peace and quiet. I’d never watched TV before, and I couldn’t follow what was going on. Daktari was particularly perplexing.

One grizzly afternoon I watched Rolf Harris jumping up and down with a cardboard cut-out yellow submarine. The Beatles had just released “Yellow Submarine”. It was memorably try-hard.

This was my first encounter with Beatles music. I was a cranky, sick five-year-old. I wasn’t disposed to be amused.

Angels and Batman

In December 1966 our family flew back to New Zealand. My parents were in full agreement that we would never again set foot on the Northern Star.

We stopped en route in Pasadena, California, to have Christmas with my American grandparents, Adeline (Mormor) and Fred Hirsh. I believe they had lent my parents the money for our air tickets.

Our grandparents were overjoyed to see us. Mormor was especially doting. Grandad was grumpy, because he had Parkinson’s. When he stood up, he leaned over and wobbled.

My grandparents’ Mission-style house on North Holliston was like Santa’s grotto, crammed with angels, reindeer, nativity scenes, fake snowmen, tinsel and gingerbread cottages.

My brothers and I were put in front of a black and white TV in the small living room at the back of the house.

In the main living room Grandad was sitting in a thicket of reindeer and holly, watching the news on his new colour TV. The newsreaders’ faces were green. My grandparents were still getting the hang of the settings.

American television seemed much more compelling to five-year-old me than the BBC. It was like Froot Loops (which featured frequently in the ads), while the BBC was Weetbix.

Batman and The Monkees were the latest shiny TV programs for kids. My mother was excited about a radical new show for grown-ups called Star Trek, but I didn’t get to see it.

And we all watched the very first screening of How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Spinning teacups

The next day my mother’s sister Aunt Mary took us to Disneyland.

I knew Walt Disney’s theme park was a big deal, but I wasn’t expecting anything familiar. I’d already figured out that Southern California and England (and New Zealand too) were parallel universes. There was very little that I could map across from one to the other. Including table manners.

Also, at five years old I’d never seen a Disney movie, never met Mickey Mouse or Donald Duck. There was no sign of the TV characters I did know something about: the Flintstones, Batman, the Grinch.

We arrived at the Alice in Wonderland themed area. I did know about Alice. I was reading Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland with help from my father. It was uncomfortably close to how I experienced my life.

But it turned out that there was a parallel universe Alice in Wonderland too!

I discovered that Disney’s Alice film had little in common with my book. Giant teacups?!

Aunt Mary and David and I clambered into a huge pink teacup. We sat down. A metal bar locked the exit so we couldn’t fall out. And then it started to spin. Round and round and round….

I held Aunt Mary’s hand and held onto my breakfast. At least I hadn’t consumed any chocolate.

It felt like an appropriate ending to a very strange year.

Above: Spinning teacups at Disneyland. This is how it ended – a tea party with nothing to drink. It still didn’t make any sense. Photo by Ellen Levy Finch, CC BY-SA 3.0

About Alice

I’m a life coach and musician.

Find out more here: About Alice.

Would you like to hear more from me?

Join my email list and I’ll send you a copy of my ebook, 12 Creativity Hacks for Musicians.

It’s full of my favourite tips for regaining your feeling of playfulness. Here’s where you sign up: 12 Creativity Hacks for Musicians.