Saturday afternoon is my favourite time of the week. My ukulele group meets at 4pm. We drink a glass of wine, play ukulele and have fun. For two hours, nothing else matters.

Our nine members have a wide range of musical experience – some have been playing for six months, some for six decades. Our folders are bulging with music and we’re always finding more.

This weekend we played “Mamma Mia”. I’ve never been much of an Abba fan, but I’ve come to appreciate them via the ukulele. Two recent additions that we’re working on are Ed Sheeran’s “I See Fire” and “Black Silk Ribbon”, a nasty gothic murder ballad by Bic Runga and KT Tunstall. Anyone can bring music to the group.

A lot of factors converge to make the ukulele a wonderful instrument for our times. It’s a small portal to a world of music making. It’s absolutely the fastest way to start making music that I’ve ever found. It’s possible to go from scratch to playing music confidently in just a few months.

Hooked for life

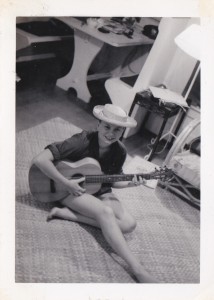

I first played the ukulele when I was six years old. My mother, Sue, showed me three chords, and I was hooked for life.

Sue learned to play ukulele and guitar in Hawaii, a couple of years before she arrived in New Zealand in January 1957. She was a young folk guitarist, just ahead of Bob Dylan. She sang, played and even wrote songs – we have a couple of her originals, captured on vinyl.

From that first exhilarating day when I learned “My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean” (shortly followed by “Morning Town Ride”, which was a favourite in my primary school class), I could see clearly that the ukulele was my ticket into a wonderful world of music.

But having started me off, mum didn’t follow up. She gave up making music soon after. I think she just didn’t have enough time. She had three youngsters, and over and above this, a huge passion for being an archaeologist. (She was the first archaeologist to do fieldwork in the New Guinea highlands.)

Instead, I was sent off into the classical music world. I spent the following 15 years playing violin and viola, in symphony orchestras and chamber music groups. The music was beautiful, but a lot of the time it wasn’t much fun. Orchestras were bitchier than high school, all the players had sore backs, and a talented viola player in the year ahead of me at university failed her final exam for playing Bach in the wrong style.

After dropping out of music school in my early 20s, I went wandering across the United States, and ended up playing bluegrass fiddle in a bar band in Montana. (Which was fun, while the summer lasted.) After returning to New Zealand I found my way into alternative rock bands, playing violin, bass, drums and/or keyboards in various rock bands for 20 years.

All these musical adventures were fun on many levels, but fun was never the main purpose. The ukulele, on the other hand – there’s no other reason for it.

Not serious

The ukulele is a very democratic instrument: it’s cheap, simple and not difficult to learn. Many fans of the ukulele, including performance artist and musician Amanda Palmer, have pointed this out. The ukulele is acoustic – you don’t need electronic gear; and it’s not loud. When you play, you won’t drown out the neighbourhood.

Ukuleles are even fairly easy to make, if you have good woodwork skills (although I certainly couldn’t do it!). I know some wonderful men who are making ukuleles for their grandchildren.

Not everyone loves ukuleles. Many professional musicians and music teachers regard them as kids’ toys and beginner’s instruments – a place to start, but not the main course. Not “real” music; not “serious” music.

But this is one of the ukulele’s great virtues: because it’s not serious, it’s easier to start making music. The bar is a lot lower. With just about every other instrument there’s an expectation that you’ll have a certain level of skill before you show up in public. With the ukulele, all bets are off, straight away. There’s nothing to lose – and a lot of fun to be had.

The ukulele is a way into participatory music making, that works for people at all levels of experience.

For a skilled musician like George Harrison of The Beatles, the ukulele was a route back into music as play – regaining the sheer joy of making music with friends. Paul McCartney says in The Concert For George: “Sometimes when you went round to George’s house, after dinner the ukuleles would come out…”

For absolute beginners, who’ve never played an instrument, it works equally well. And for everyone in between.

High-profile ukulele groups that perform in public seem to be a bit self-conscious about this requirement to have fun, and emphasise the quirky and wacky in their performances and repertoire. I think some of them try too hard. But I guess being freed from the expectations of perfection and virtuosity makes a lot of experienced musicians feel uncomfortable. (Maybe audiences too.)

What the ukulele does

Playing the ukulele is different from other kinds of music making that I’ve been involved in.

- Ukulele playing is (mostly) participatory, rather than performance based. Rock/pop music and classical share an emphasis on practicing for a performance.

- Ukulele playing doesn’t require reading music (in fact this isn’t particularly useful). It shares this with rock/pop music making. Having said this, everyone in my ukulele group has folders bulging with song charts with chords and lyrics, because many of the songs we play have complicated chord structures and lyrics that that we haven’t learned by heart.

- Ukulele playing gets people singing without being self-conscious about it. Classical, rock/pop and folk genres all emphasise “good” singing, and many skilled instrumental musicians avoid singing, because they don’t think they’re “good enough”.

- Ukulele playing reclaims popular music for participation. We’ve had more than 50 years of listening to recordings. Playing ukulele is an opportunity to “own” popular music by playing it. When you know four chords, that’s enough to play many pop and folk songs. (With the notable exception of The Beatles.)

- Amanda Palmer points out that the ukulele is also a great medium for songwriting.

Polynesian strum

For those of us who live in the Pacific, the ukulele is part of our cultural landscape, as well as being part of the bigger picture of international popular music. Ukuleles were popularized by Hawaiians, but there are other significant Polynesian contributions to ukulele music in the innovative rhythmic strums.

Perfect imperfection

The Japanese concept of “wabi-sabi” refers to “the acceptance of transience and imperfection”. It normally means something like the flaw in a beautiful handmade pot, which makes it even more beautiful, but I reckon it also applies to the ukulele very well.

Because ukuleles are imperfect.

A musician friend commented to me that ukuleles always sound a bit out of tune, even when they’re tuned properly. This is true, but I don’t think it’s a problem.

With ukuleles, more usually sounds better. This is very different from most other kinds of group music making, where the players need to have a pretty high degree of skill in order to play together effectively.

Even with modest playing abilities, a group of ukulele players is greater than the sum of its parts. (Okay, as long as everyone’s on the same page!) Somehow, the minor imperfections blend together into harmony.

Perfection in imperfection.